"It Is Just So Validating to Have Books in the World"

A conversation with Amy Shearn, author of "Dear Edna Sloane," about writing fiction, the challenges of a literary career, stoned teenagers, Thomas Pynchon making Uber deliveries, and much more

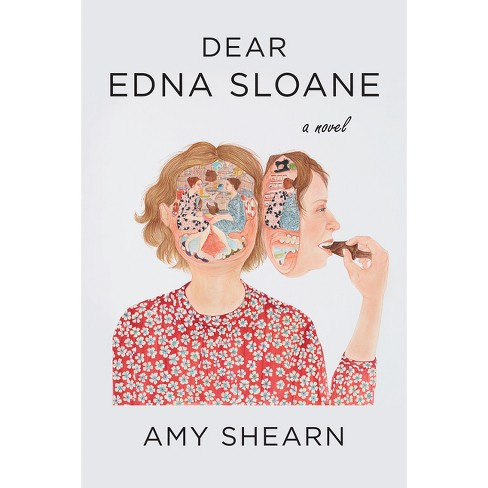

Humblebrag alert: I am #blessed to sometimes receive emails and texts from Amy Shearn. They are full of wordplay and literary references and dumb jokes and stray witticisms, and are a sheer joy to receive. I feel sorry for the rest of you who are not as lucky as I am to have Amy in my inbox, but fear not; her new novel, Dear Edna Sloane, ably recreates the sensation. This epistolary novel ingeniously follows the efforts of Seth Edwards, worker ant at a click-chasing literary website, who is trying to line up an interview with Edna Sloane, a celebrated 1980s wunderkind who disappeared after writing a beloved debut novel. As it turns out (modest spoiler alert, but one endorsed by the author herself), Edna has not disappeared at all. “You want to become anonymous?” Edna later asks us. “Easy. Be a mother.” Shearn’s fourth novel is a triumph, an extraordinarily funny and heartfelt book about literary aspiration, aging, divorce, Jewish identity, what it might mean to compile a viral James Baldwin listicle, and so much more.

I recently had the chance to catch up with Amy and talk about her book. She kicked off our chat by admiring my $12 Parker pen: “I have a Bic with a chewed cap in my bag. I’m going to go buy a pen after this. I need to respect myself.”

This is a book about the allure and perils of literary success. What does it mean to you to be a successful writer? I think many of us start with the idea that we will write a book and it will change our lives.

I do feel like I had that thought when my first book came out. I was never expecting money. I was never expecting, or even actively wanting, fame. But I was definitely expecting something. I really had that feeling my life is gonna change. And it really doesn’t. You’re just a person who has a book out. It’s kind of relaxing to remember that.

[But] It’s easy to forget once you’re publishing books, that it is just so validating to have books in the world. For so many writers, that is their dream.

My fifth novel is coming out next year. And [students will] be like, ‘Oh, so you just write all day?’ And I’ll be like, ‘No! Oh no. Still no. I still am teaching and working all the time, and still just fitting writing in when I can.’

Perhaps that’s some of the value of having a literary community. It serves as a reminder that even successful writers are working other gigs to keep it all going.

Isn’t it funny, though, that we still have this idea that novelists can just novel all day? And I don’t know if anyone can do that. Maybe there’s, like, three. There’s Stephen King, and maybe Danielle Steel.

Thomas Pynchon.

He’s, like, editing a client’s manuscript.

Making Uber deliveries.

Even the successful writers you know are teaching. That’s probably for the best.

So what does literary success consist of?

I feel like, realistically, it’s always getting to write the next book. Having my life set up in a way that I’m able to write the next book, and that it won’t be a fucking struggle of epic proportions to find a publisher for it, which might just not be a reality. That might just be how writing life is.

This book feels like a real triumph for you. It’s so funny, sharp, and full of life. What went into developing these two distinct voices of Seth and Edna, each of whom are wondering whether writing is a worthwhile pursuit anymore?

It feels wrong to say, but it was actually a pretty easy book to write. I wrote the first draft in under a year, which never happens for me, because I don’t have that much writing time. It was writing to amuse myself, that first draft. And that’s where Edna’s voice came to me, and started talking to me about why do we write, and why do we keep writing, and what is the point of doing this.

They’re kind of two sides of the same consciousness. He’s this hungry writer who’s just starting out, wanting to know what’s going to happen. How is life going to be? In some ways, she’s much more established, but in other ways, she understands his point of view so much. She also needs to keep herself motivated. But I feel like it was the book I wanted to read. I realized, too, [that] so much of it is pep talks to myself.

Edna is so distinctive a character. Were there particular literary role models you had in mind in creating her?

I feel like she’s an amalgam. I feel like she’s J.D. Salinger/Alice Munro/I don’t know. My publicist at Red Hen told me that “The only authors who don’t have to think about their own publicity were famous before the internet. It’s just the truth.’ But those of us of a certain age remember that time. ‘Well, does Jennifer Egan have to post on Instagram?” No, but someone else is doing that for her.

Was the style of the book epistolary from outset?

It just came into my head that way, this voice. From the start, it was letters back and forth. The plot of the book is really simple. She’s missing, or considered missing, he’s looking for her, and is he going to find her or not, and what’s going to happen? The story structure is so simple that that gave me the flexibility to be more playful with the form. It was a really fun way to write it, in these fragmented bits of time that I had to write. At the time I was on an editorial staff, working full time. I basically had lunch breaks and little bits of stolen time. So I was writing something in a really fragmented form. It really worked well with my writing life at the time.

It's like, ‘I have 45 minutes. What can I write?’

I think it’s always true that the shape of your life affects the shape of your book. I tell students that, too. They’ll say, ‘I want to write this sweeping, three-part epic, and I have 15 minutes a day to write.’ I say, ‘OK, I’m not saying you can’t write that, but what if you right-size the project for how much time and energy you have for it? Do you have little fragments of time? Do you have one weekend a year where you can be an art monster? Do you have every other weekend? And what kind of project will fit that?’ I’ve always been a very pragmatic writer.

That pragmatism is essential in moving a project from 10% done to 99% done.

People are so disappointed when you tell them the way you write a book is you write a little bit of it, and then more and more and more.

I feel like people are very hungry for a formula. The internet has really fed that. What if I get this software? Will it help shape a novel?

Much of the second half of the book is about the rigmarole of family life. Was it fun to tackle that topic? Or did it feel like scraping at wound?

It is something I was thinking about, and all novelists who are parents, or mothers, probably think about it. How weird it is to balance your creative self and your self that lives in the world. I hear students say, ‘I really want to write this, but what if my aunt reads it and judges me, or what will my coworkers think?’ Hopefully that’s a very small portion of your readership, but also you do have to forget about that, and ignore that. ‘The other PTA moms might think I’m a real asshole if they read this book, oh well. It’s embarrassing to be alive.’

Mothers who are writers get asked ‘What do your kids think of your work? How do you balance writing and motherhood?’ I don’t think dads get asked that very often.

Never, in my experience.

My kids were at my book launch last night, they’re like, “Hey! There’s cake? Mmm. Why isn’t it chocolate? OK, thanks, bye.”

I think that’s very healthy. How interested are kids in their parents? I still don’t know what my dad’s job was. Who cares! He’s a dad. I don’t think it’s that interesting to them.

We actually don’t want our children to be aware of our anxieties, or our struggles.

Someone asked me once what would your kids say about having you as a mom. I asked my kids that, they said, “Um, she’s usually wearing a sweatshirt, and telling us to eat vegetables and go to bed.”

There was a long lag from writing this until it was published. I was still married when I was writing the first draft. It’s interesting to me now to go back and read the parts about [Edna’s] marriage. “Oh! Someone was processing something.”

I do think with fiction, you work things out on the page that you’re not always aware that you’re working out on the page. It’s lightly horrifying how much of the texture of the inside of your brain [is revealed], even when you’re writing fiction. Nothing that happened in this book ever happened to me, really, except for working at digital media sites and wondering what I am doing?

It was interesting to me to note how Jewish this book is. Edna struggles with being a writer not only for reasons having to do with literary success, but also with the legacy of her family history. Do you feel like you are inheriting the mantle of the American Jewish writers of the past, like Roth and Malamud?

Maybe novelists are like New Yorkers, in that they’re kind of a little Jewish, whether they are or not. I do think it’s my most Jewish book I’ve ever written. The main character, as you know, her father is a Holocaust survivor. Which is not something I have experience of in my family. My family was all here before World War II. But of course, growing up as an American Jew you’re soaked in that backstory.

It is the first time in any of my books I’ve palpated what that does to a family and to a person and to a community. Also, in the narrative of the book it gives Edna this useful backstory that adds to why she has such a complicated relation with her writing life. People who have come from such uncertainty and are like, ‘All we want is a normal life.’ And then they have this kid who’s like, ‘Why would I want a normal life? I want to be an artist.’ The pressures for her are different than if she came from an artsy family that was like, ‘Great honey, go and get an MFA in fiction writing!’

You write near the end of the book “How many seemingly ordinary folks contain multitudes.” Is that a kind of credo here, for Seth and Edna, and for readers, as well?

It just makes me think everybody has a complex inner life, where interesting and sometimes weird things are happening. Just novelists sell those to people. But everyone— I think! I hope! —has a rich interior life, and it’s weird how quick we are to flatten people out. I see this Instagram post, and this must be all you are. Someone is more than their outfit, or their persona, or their job title.

Maybe as we age, we lose touch a bit with that inner core of ourselves.

That’s been so interesting for me. I got divorced when I was 40. [I’m] dating in my 40s, really for the first time in my adult life, and it’s this whole new kind of emotional skillset. I’m going to interact with all sorts of people, and have emotional states that I didn’t know I could still have. I associated them with being a teenager, because that was the last time I had a crush or whatever it is. Lifelong learning. I could have just done crosswords or something, but no.

Your book is really funny, but also has a deep well of yearning inside of it: for love, for meaning, for depth. It seems to be wrestling with questions like ‘What does it mean to write a good book? What does it mean to live a good life?’ Sometimes books shy away from these earnest questions.

Right. It’s a question you ask when you’re 25, but when you’re 45, it’s embarrassing. What am I, a stoned teenager? So many of us are, in a weird way, creating our lives from scratch. The part of that that remains imprinted on our consciousnesses is like go to college, go to graduate school, get a job, get married, buy a house, have kids, and so much of that is so irrelevant to so many people. It’s also hetero and conventional and just out of reach to so many socioeconomic levels. So what are you left with? When you’re making it up as you go, how do you know you did a good job?

Amazingly, your next novel is already scheduled to come out next year. What will it be like?

I always feel like with every book, I’m doing with something totally different: totally different voice, totally different characters. And then I think someone else would read them and say, yeah, sounds like you! These are the same things you keep chewing over. It’s set over the summer of 2020 in New York City, and it’s a woman who gets divorced and then the pandemic starts. And she’s dating on apps for the first time in her life, but she’s an app designer, and she thinks, ‘Hey, I don’t really want to pick from who’s available, I want to make my own perfect person,’ so she creates this AI chatbot, which felt like science fiction when I started four years ago.

You’re so funny in your email and text correspondence, and Dear Edna Sloane conveys that same sense of playfulness.

I think it’s easier to be funny in the first person, because so much of it is about voice. When I would be workshopped in graduate school, people would say this was funny, and I’d say, ‘Oh! Was it? Yeah, I did that on purpose. Why was that funny?’ And trying to pick it apart in that very unfunny way, like what made that funny? What made this land but that didn’t?

I love a book that is a mix of funny and sad, and lightness and darkness, and humor and serious topics. The publishing industry is often a little confused by it. Is this literary? Is this commercial? I was really conscious, too, of wanting to write a light, funny book that someone could read in one sitting. Because I feel like I love books like that so much.

But your funny book is also about divorce and Holocaust survivors, though.

Holocaust survivors, [but] make it funny, which is the story of our lives, I guess. It’s also just interesting and something I have no intelligent thing to say about the fact that this book is coming out now, and being an American Jew is very fraught. I am too dumb to say anything other than I hope everyone is OK.

It seems like part of what you’re describing in the book, as well, is the way in which communing with art seems to get harder as we get older. Seth may not have written much of anything yet, but it seems easier for him to access that sense of beauty in art that Edna struggles with.

Someone asked me recently if I’m still able to read books as a pure reader. It’s hard to get there sometimes because I’m such a critical reader. It helps me to look through used bookstores, find a writer I’ve never heard of, I have no context for, read something in translation, just to have something where I’m able to read it out of context. I also feel like I’ve maintained my amateur love of other art forms. I don’t want to become a critical movie watcher or a critical art-museum goer. I need to maintain some parts of my life where I’m like, ‘that’s pretty.’

As people who love art, we want to find a way to channel that sense of awe before something that activates something mysterious in our minds.

I don’t know if you’ve ever done Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. It’s like rehab for blocked writers. One of the things she talks about is doing a weekly artist’s date, spending even an hour doing something that awakens your sense of awe. She suggested going to a pet store and looking at birds. Going to a beautiful garden. Going to a museum. Listening to a beautiful piece of music. Doing something where you say, ‘I’m not going to think about writing. I’m just going to experience this beauty.’ And turning off that writer part of your brain that’s like, ‘Do I have a take on trees?’

Saul this was so much fun! Thank you so much!